That is what Hélène Cyr missed most: human interaction.

I look over at the woman sitting across from me. The only features I can see are her thick hair gathered in bouncy curls and her eyes, sparkling when we first met, downcast now, after remembering those first days of the pandemic.

I nod, acknowledging the new social rituals replacing familiar ones. We are sitting for a chat “a hockey stick” apart, faces covered by masks.

Earlier that day, I noticed two friends meeting on the street by chance (judging by the excited chatter emerging from behind the masks). They ran towards each other with open arms only to stop suddenly a couple of steps apart. A visible awkwardness put a damper on the initial warm encounter, and instead of hugging, moments were lost trying to break the bodies’ forward momentum and to control the limbs which still wanted to close the distance between them.

Well, these days, friends cannot just “bump into each other” anymore. It was comical and quite sad.

I also realized that I’ve been lucky. When words like “cohort” and “bubble” organize social life, I have my own family to provide the human touch, the necessary embrace, the day-saving smile. But what if your family does not live near you?

“All my life I’ve been surrounded by people,” says Hélène. “I taught French Immersion, my days spent among my students. After I retired, I kept busy, grateful that finally I have time to do what I always loved most: hiking and skiing with my friends, visiting my family, travelling, and making art. I took classes at artsPlace and almost every day I was walking to my little studio, spending happy hours painting and experimenting with colours.”

“And then in March last year my life came to a halt.”

She’s opening a spiral-bound sketchbook and shows me the first page covered in her neat, black writing. The title: …” and the World Stopped…Timeline of the coronavirus pandemic” and underneath, columns of dates marking the spreading of the virus across the globe.

The only colour in this monochromatic litany of numbers of COVID-19 cases and deaths is a yellow highlighted entry to which she points: “15 March 2020 – confinement and social distancing in Canada”. She puts down the journal:

“That was the moment when the global crisis became personal.”

“I was in a state of shock. I was worried about my loved ones, about myself, contracting the virus, contaminating someone else. ‘Keep your distance’ was everywhere, on the radio, in the news, on the doors. I kept my distance but after a couple of weeks I was missing my family, my friends’ hugs, the small talk at the grocery store, just seeing faces …”

Hélène’s eyes are misty. I want to pat her arm, but that simple human gesture of support feels so …loaded these days, so I don’t.

“And then I stopped painting. I just couldn’t”, she continues. “For me painting is joy and all around the world people were getting sick, and dying, and I just …I don’t know, it didn’t seem right…to paint.”

She started a diary, just to keep her mind busy, her hands working. She was listening to the radio one day and some words formulated the question she didn’t know she was asking herself all along:

“How relevant is Art, right now?”

And with a jolt, she heard the answer “Bearing witness is what artists do”.

When she quotes the words, she transforms. Her eyes open wide, full of light, her curls flutter joyfully: “That’s when I realized that if I keep painting, I am not being frivolous. That art matters, that my art is significant to me, it helps me keeping the chaos at bay, making sense of it. “

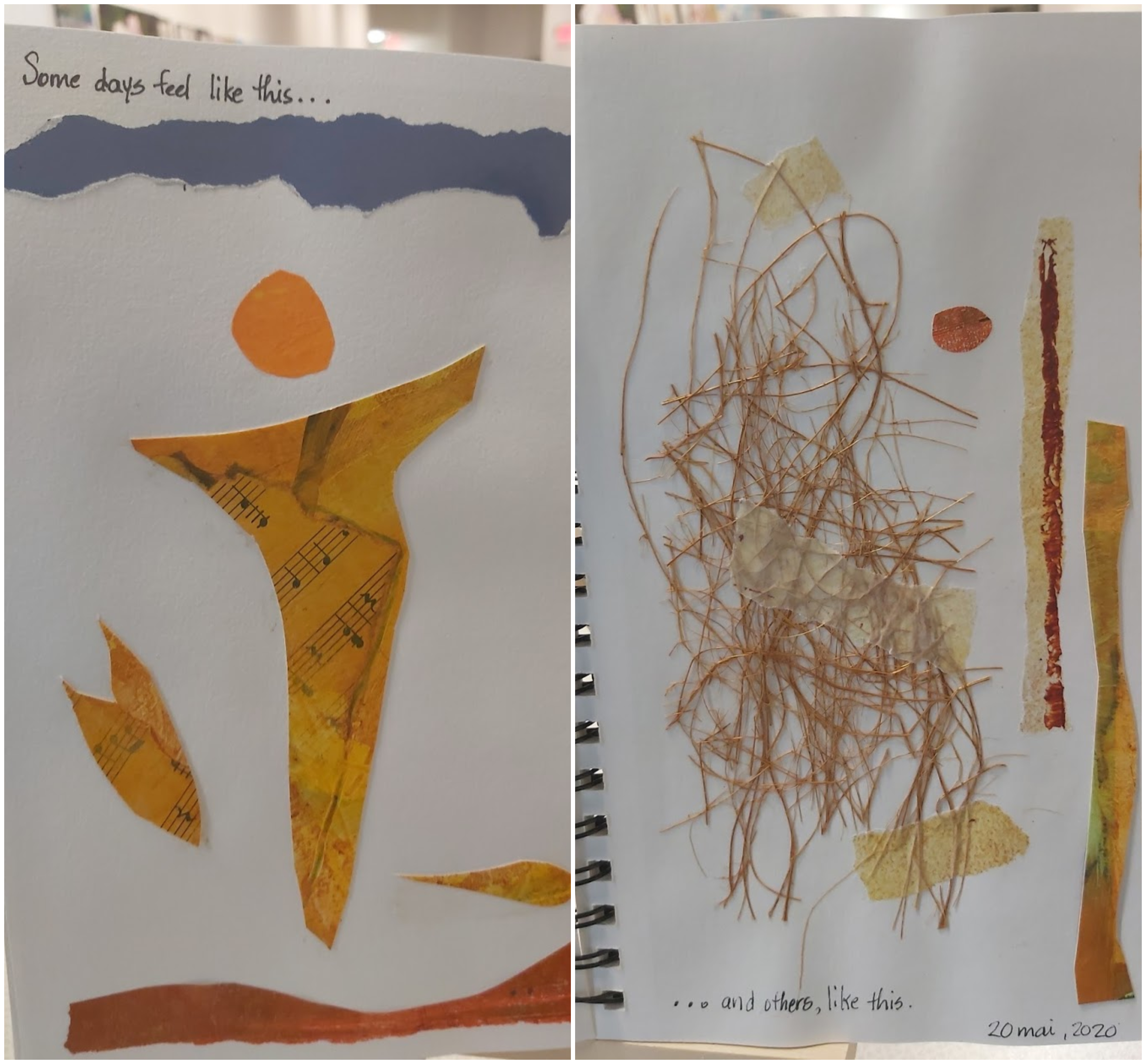

The next pages of Hélène’s journal are more visual: collages, ripped pieces of paper dotted with musical notes re-invented as branches and tree-tops; acrylic layers carefully separated or furiously mixed.

The worry, the frustration, the confusion is still there. “Some days feel like this…” and a dancing golden silhouette is soaring with open arms embracing the world, followed on the next page by confusing, tangled, mixed-up threads with the note “…and others like this”.

But now these feelings are expressed and contained, giving Hélène the energy to look around, and to hope. She joined an internet choir, she sings along with the radio, she dances by herself, she takes socially distanced walks with her friends, she paints. She lives.

Her journal, monochromatic in the beginning, is a kaleidoscope of colours now.

What is Hélène doing next? She laughs, delighted: “I am going to play with the blue and green paints. There’s so much to learn, and to discover still…”

Story written by Maria Gregorish, March 2021